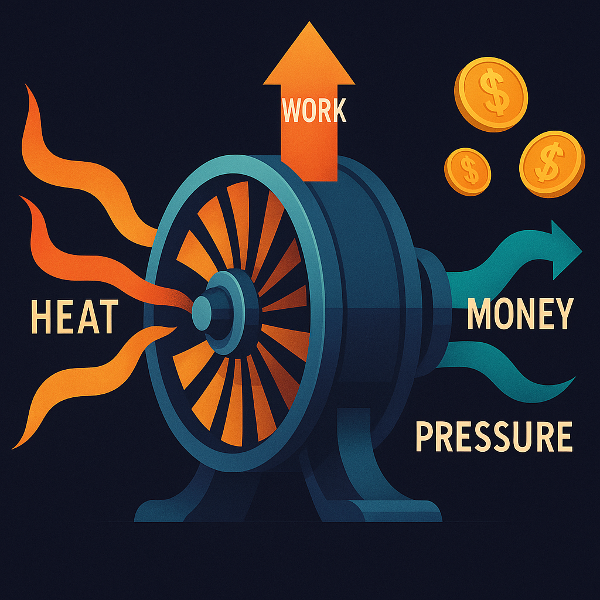

A heat engine cannot operate in a vacuum.

It must release heat to an environment.

For locomotives, the surroundings are air—a poor coolant.

That’s why locomotives are inefficient and need constant refilling.

For submarines, the surroundings are seawater—a powerful coolant.

That’s why submarine reactors sustain a closed cycle indefinitely.

The economy works the same way.

The financial sector is the surroundings.

It:

- absorbs the heat that firms release,

- redistributes it as credit, deposits, savings, speculation, and investment,

- cools overheated sectors,

- warms cold sectors,

- and maintains the temperature gradient needed for engines (firms) to run.

If the surroundings are “air-like” (shallow financial system):

firms cannot run closed cycles.

They must burn capital and constantly seek new financing.

The economy becomes volatile and inefficient.

If the surroundings are “water-like” (deep financial system):

firms can run closed cycles, recycle capital, grow smoothly, and innovate.

The economy becomes stable and scalable.

Banks are open-cycle engines in the environment.

Banks:

- take in deposits,

- push out loans,

- absorb losses,

- require capital injections in crises,

- and depend on constant flows of heat (repayments, interest, deposits).

They are open-cycle processors of environmental heat, just like industrial locomotives.